[The following article from 5 March 2016 is reposted here because of an outage of the website for The Economist. It is provided here by utilizing the Google cache version of the article. Visit subscriptions.economist.com to learn more about digital and print subscriptions, because… “Two thirds of the world is covered by water. The rest is covered by The Economist.”]

POLITICAL parties are never monoliths. As those inside them are ceaselessly aware, they are fractious and fractured. And yet, especially in two-party democracies, they endure. A mixture of delivering the goods their voters desire, dividing spoils between internal factions and adapting to external change allows them to overcome their centrifugal pressures. They even manage, much of the time, to look more or less coherent while doing so. For most of the 20th century most Americans knew, more or less, what their two parties stood for.

These times, though, are out of step. Though political scientists proved slow to pick up on it (see article), America’s parties are more fragmented than usual. The state of the Republicans is particularly parlous. But the contradictions among Democrats, though less obvious, also run deep.

Donald Trump’s run for the presidency has prospered despite lacking all the things parties usually provide for a front-runner: not least strategists and policies, money. It is hardly surprising that the Republican Party failed to see Mr Trump coming. What is odder, and much more culpable, is its failure to address the mismatch between its grassroots supporters and its policy agenda into which Mr Trump has tapped so effectively. In its subsequent disarray, the party has come to resemble a newspaper that has just discovered that its readers no longer need it to mediate between themselves and the world.

The Republican Party arrived in the 21st century as an alliance of small-state, low-tax, pro-business voters with religiously inspired social conservatives and national-security hawks. It enjoyed a disproportionate popularity among white voters, the result of its successful recruitment of southern whites who disliked the innovations of the civil-rights era and, under Ronald Reagan, of blue-collar workers across the country. This mixture of interest groups had proved pretty successful: it held the White House for 28 of the 40 years from 1969 to 2008. During this time the pro-business lot were the senior partners in the arrangement, not least because they paid for the party’s election campaigns.

This is the first primary season in 50 years where that has not held true. The Koch brothers, who have built the wealthiest network of political donors in America with the aim of electing Republicans who will cut regulation and taxes, disapprove of Mr Trump. They have said they will not fund his campaign; and yet he thrives.

Faultlines exposed

Mr Trump’s ascendancy cannot merely be ascribed to his wealth—though that certainly helps, by allowing him to appeal directly to the concerns of the base rather than those of his donors. He has exposed faultlines within the different camps, as well as between them. Even before his rise, some pro-business Republicans were beginning to despair of the party, the congressional wing of which seemed to enjoy nothing more than shutting down the federal government and playing chicken with the debt ceiling. After the financial crisis, when a Republican-led administration bailed out several large financial institutions, denunciations of crony capitalism became a Republican theme as much as a Democratic one. Mr Trump has deepened the divide on the business wing. In December the head of the national chamber of commerce said he viewed Mr Trump’s candidacy as a form of entertainment.

He has also spilt the social conservatives. A libertine history and the look of a rouégone to seed would not in themselves preclude the support of evangelical Christians, who are, after all, keen on repentance. But Mr Trump is not very religious and does not go out of his way to seem so; his adoption of pro-life positions seems insincere. Christian Post, the country’s most popular evangelical news website, recently ran an editorial with the headline, “Donald Trump is a scam. Evangelical voters should back away.” Hitherto powerful socially conservative organisations such as the Family Leader have endorsed Ted Cruz, a Texas senator, instead. But such exhortations have had little effect: Mr Trump has won comfortably with self-described evangelicals in most states.

The reason evangelicals vote for Mr Trump has little to do with faith or specifics of policy. It is more a question of attitude. A study by the RAND Corporation, a think-tank, has found that the most reliable way to tell whether a Republican voter was going to support Mr Trump was whether he agreed with the statement: “People like me don’t have any say about what government does.” Trump voters feel voiceless, and whatever attributes Mr Trump lacks, he has a voice. He lends it to them, to express their grievances and their aspirations for greatness, and they love it.

It is also a voice that says things which other politicians do not, such as that Mexican immigrants are likely to be drug-dealers and rapists. Such untruths fit into a broader, if largely tacit, racism that has made Mr Trump popular not only with the Ku Klux Klan, but also with the considerably larger number of whites who harbour some racial resentment. Geographically, his support correlates with the frequency of racial epithets in Google searches.

The weakest of the three Republican factions, the defence hawks, might even prefer a President Hillary Clinton to a President Trump. Mr Trump’s constant refrain about American troops always losing, his tendency towards isolationism, his insulting of prominent veterans such as John McCain, his attacks on George W. Bush as commander-in-chief and, most of all, his apparent enthusiasm for soldiers committing acts that would have them court-martialled, are a recipe for these Republican voters to the Democratic camp.

Again, though, part of Mr Trump’s appeal reflects what at least some Republicans like about hawkishness; its association with authority. The Republican Party has spent the past half-century opposing the might of the federal government in every arena other than foreign policy. It now faces the prospect of going into the election led by someone who, surveys suggest, draws his most ardent support from those who would like a more authoritarian president in the White House. At that point it would be hard to say what, if anything, the party stands for.

A battle of generations

Mr Trump’s ability to blow Republican cracks asunder is unprecedented. But it has been helped by a long-standing unwillingness to face and fix those contradictions. For years the party has concentrated instead on opposing Barack Obama’s policies and, indeed, his legitimacy. With Mr Obama on the way out, that is moot now.

He has, however, helped Democrats to know what they must jointly do. As Republicans long to tear down achievements they associate with Mr Obama, Democrats want to protect and uphold them. This has tended to keep the members of the party’s own coalition in agreement. Yet the ties between the voting blocs that favour Democrats—Hispanics, blacks, those with postgraduate degrees, single women, the non-religious, union members and millennials—are subject to change. The primaries have also revealed a powerful urge among activists to move the party leftward.

Democrats fare exceptionally well with non-whites: in 2012 one in four of those who voted for Mr Obama were in this category, compared with one in ten of those who voted for Mitt Romney. But the interests of blacks do not always align with those of Hispanics. Fearing more competition for low-wage jobs, the congressional black caucus, allied with the unions, was partly responsible for defeating a push for immigration reform under George W. Bush. The party has found ways round this clash, presenting immigration reform as a question of civil rights; when Mr Obama meets caucus members, immigration reform tends to be omitted in a mutual show of good manners. But the division remains.

The current crop of primaries has also made it clear that Democrats are divided along generational lines. Bernie Sanders has thrashed Mrs Clinton in every contest among voters whose formative political experiences were the Iraq war (which she supported) and the financial crisis (blamed on her Wall Street supporters). For those born before the Reagan years, by contrast, the fact that Mr Sanders honeymooned in the Soviet Union disqualifies him from consideration. Older Democrats remember the party’s move to the centre in the 1990s as pragmatic, correct and fruitful; younger ones consider it a betrayal.

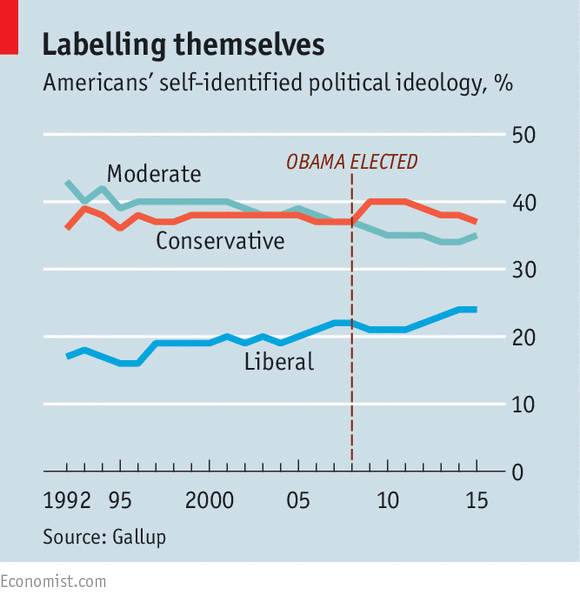

When its members actually turn out to vote, the Democratic coalition is still formidable. Non-whites make up an ever-increasing share of the electorate. Polling by Gallup shows that the number of Americans who describe themselves as liberal has increased over the past 20 years, while those who call themselves conservative has held steady (see chart.) Self-declared moderates lean Democratic. But often—especially in non-presidential election years—the coalition can’t be bothered.

This has led to a party unable to refresh itself. Were Mrs Clinton (68) to win the nomination and then fall under a bus or an indictment, the names often mentioned as possible replacements are John Kerry (72) and Joe Biden (73). During Mr Obama’s presidency Democrats have lost 900 seats in state legislatures, 11 governors, 69 seats in the House and 13 senators. This helps to explain why Mrs Clinton has had no young pretender to voice the opposition to her from within the party. Mr Obama relied on his own apparatus, separate from the party, in his two presidential campaigns. Mrs Clinton has vowed to rebuild the party if she wins. But that supposes that its constituent interest groups continue to see the Democratic Party as the best way to get what they want. Once the presidential election is over, they may find apathy more attractive again—not least because, now that it has acted on heath-care reform and (to an extent) on climate change, the party has been remarkably poor at setting out new worlds to conquer.

There is nothing immutable about the way the two parties currently line up. Republicans used to be the big-government progressive party, formed in opposition to slavery and pushing to remodel the South after the civil war; they have also been the small-government party, not only now, but in opposition to the New Deal in the 1930s. Democrats were once the small-government party, opposing those who wanted a more powerful federal government and defending the interests of white southerners against Washington; now they are famous as the big-government party, pushing federal anti-poverty programmes in the 20th century and government involvement in health care in the 21st.

Furniture-moving

This election could see the furniture rearranged again. Some Republicans wonder if a Trump candidacy might redraw the electoral map, winning over blue-collar whites who don’t normally vote in rustbelt swing states like Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan or Wisconsin. If he loses, the party might still conclude that it needs to pay more attention to the economic anxieties of those who feel left behind.

For their part Democrats are counting on Mr Trump to energise members of the coalition that voted twice for President Barack Obama, and to put in play moderate Republicans, notably women, who can expect to be bombarded with Democratic messages about the billionaire’s misogyny. If Mrs Clinton marshals a broad anti-Trump coalition that peels off some habitual Republican voters and combines it with high turnout among traditional Democratic supporters, she will have an opportunity to create a new centrist coalition that may long outlast her.

Nobody yet knows whether what is happening in 2016 is an anomaly caused by the one-off political persona Mr Trump has created, or if it is tracing the outline of the future. Whatever the parties look like after November 8th, though, Mr Trump’s success to date has already changed the system, in part by proving that voters value ideological consistency (and rhetorical restraint) much less than the political classes assumed. That could be liberating, if it allows elected representatives to stray from the party line. It could be damaging if the only lines they can stray towards are brutally populist ones.

Parties exist to distil a complex set of questions into a binary choice; it is impossible to imagine a big democracy staying healthy without them. Yet in 2020, with Mr Trump in mind, the strongest candidates may start from the assumption that they do not need their parties much at all.

__________

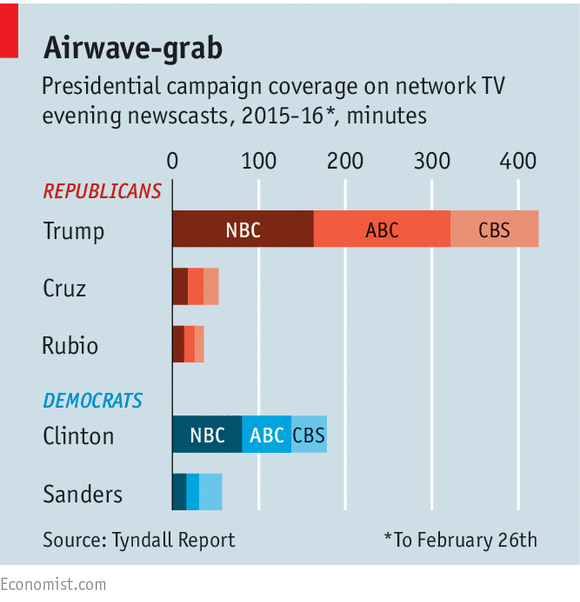

The chart below was included with the original article above.